Tao Workshop #01: Context

My name is Dave Cobbe and my blogs such as The Missing Link or Walking the Testing Talk 2.0, I talk about IT Projects that employ disconnected and non-cross-functional work-cells.

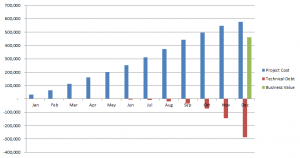

These projects suffer from miscommunication. Miscommunication leads to accumulation of “technical debt”: which makes the project cost too much and take too long to deliver too little value.

Traditional testing identifies bugs too late. Testing as a disconnected process – starting at the end of the project – cannot prevent inefficiencies from happening earlier.

One solution is to integrate and automate testing into each of the activities: analysis, specification and build as a continuous integration process.

Consequently, I would like to write a series of practical workshops about using automated testing as the main activity within your IT Projects. I hope to show the benefits when re-engineering the role of “tester” into analysis, specification and build.

Solution Description

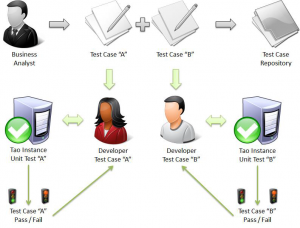

At Julius Baer, our solution is Tao by Tek-Motivation. When using Tao, testing drives development. However, contrast to other Test-Driven Development frameworks like JUnit, it is the business, using Tao, that drives testing, that drives development.

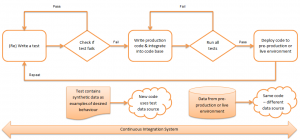

Tao will execute test-specifications automatically and return a “red-light” (test fails) or “green-light” (test passes) depending on the test results.

When developers complete their work and generate a fresh build, Tao will execute all tests over the programmer’s code and report a non-negotiable definition of done.

A “test-specification” is a structured document acting as both a specification that humans can understand – additionally, that a machine can “understand” and execute. I use Microsoft Excel to create test-specifications. The business understands Excel: and Excel gives support for automation.

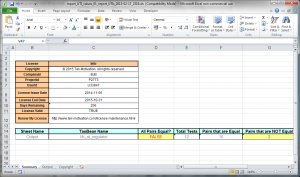

System Configuration

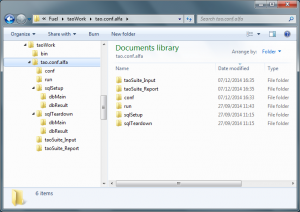

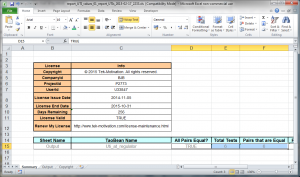

For Tao to execute a test-specification, we have to configure Tao to know what to run, what to check, where to write the test results and so on.

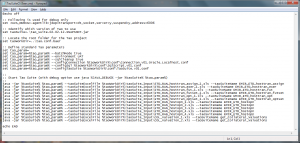

Tao needs to know which environment to run the tests. Most common is to run Tao as a “stand-alone” instance in a test environment. An example configuration could look like this:

Meaning:

- “taoSuite_Input” contains test-specifications.

- “taoSuite_Report” contains test results.

- “conf” contains parameter files, connection strings, Tao licence keys, etc.

- “run” contains system command line operations as part of your batch process.

- “sqlSetup” contains IT build artefacts.

- “sqlTeardown” contains “drop” scripts necessary to re-deploy the IT artefacts.

When running Tao as “stand-alone”, I batch the parameterisation and execution of test-specifications into a single command line, for example:

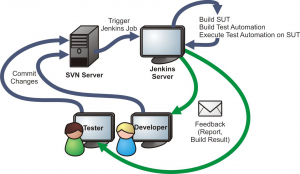

However, it is possible to run Tao in a development environment. At Credit Suisse, we used a version of Tao within Treasury Finance’s Continuous Integration server “Jenkins”.

Running Tao in a development environment makes sense when your IT Project has an automated build process: generate a fresh build when all tests pass. In addition, running Tao in development environment gives developers an almost near-immediate feedback-loop.

Use-Case: Unique Trade Identifier (UTI) Generation

So let us start with a “real-life” example. At Julius Baer, we report the trades of our clients to the financial regulator. We need to enrich the trade identifiers at source and report them in a standardised format that the financial regulator accepts – called the UTI.

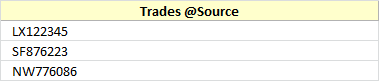

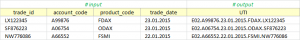

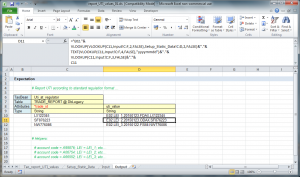

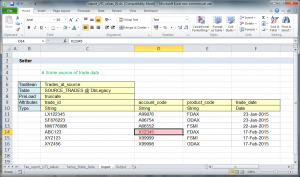

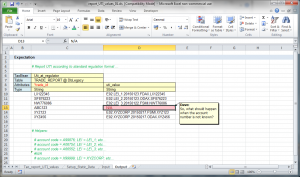

Using Tao – the first question we ask is “how do we test that?” In reply, we create a “test-specification”. Assume we have a set of trade identifiers from source:

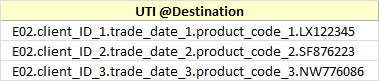

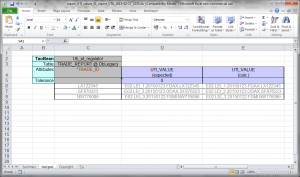

We want to report these trade identifiers as standard UTIs – with some help from the financial regulator, we now know about the E02 format:

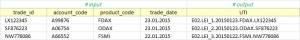

To build a UTI value, we need information besides a trade ID: we need to source a client ID, the trade date and the product code traded – for example:

Now the business can see what means “UTI generation” – but most important, the business can see two incorrect assumptions.

First, the trade date must be YYYYMMDD format (otherwise trade date = “23”, product code = “01” and trade ID = “2015.FDAX.LX122345”). Second, the account codes are actually “real” client account numbers. Banking secrecy laws prevent us communicating account numbers outside the firm.

However, we can report the “Legal Entity Identifiers” (LEI) – which are publically available global identifiers for all financial and non-financial entities. Therefore, UTI values should look like:

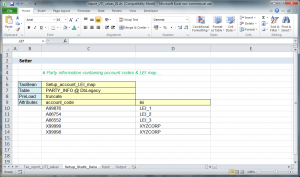

Additionally, we need an account code & LEI map to “look up” corresponding LEI values:

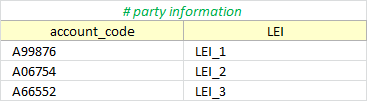

Now we can put this together as test-specification. For some given input values:

The values require concatenation – as specified – so to report a UTI in standard format:

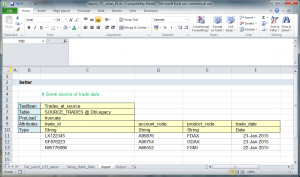

For Tao to “understand” what means input values, static data and expected output, we need a Tao Suite. This defines the input, process and output – and connects all components of the test.

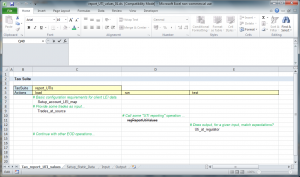

The Tao Suite of our test-specification:

Reading left-to-right top-down, Tao will “load account & LEI map”, “load trades at source”, “run operation report UTI values” (currently disabled) and “test UTI values at regulator”.

Initially, I disabled operation regReportUtiValues. As a Business Analyst, I am conscious of the line between “what” I want and “how” I want it. I may suggest the developer implements an operation regReportUtiValues but the developer may guide otherwise. Perhaps an IT operation is not necessary; other solutions like database views or Java methods may exit.

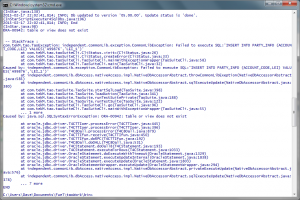

If Tao were to run this test-specification “as is”– the test fails –

Failed to execute SQL:'INSERT INTO PARTY_INFO ... Caused by: java.sql.SQLSyntaxErrorException: ORA-00942: table or view does not exist ...

For me, this is a “first” – I have never seen another framework that allows the IT Project to test program code that does not exist.

Better, the business provides testing and specification to the developer; the developer needs only to implement program code such to make this test pass.

Small digression: the more I work with Tao as role Tester and Business Analyst, the less I care how the developer implements the solution. The more Developers work with Tao, the less they care about “creating bugs” and the more confident they grow to embrace change and make radical code changes where necessary. Such a surprisingly simple premise “does the output match the expectation for some given input values (or not)” packs a surprisingly powerful punch: transparency increases as confidence and understanding increase proportionally.

Back to the use-case, I will assume the mind-set of a legacy Oracle developer and implement the transformation logic using tables and views.

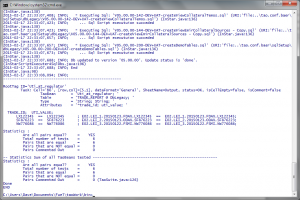

Thus, when the developer says, “I am done” – Tao will re-run the test and validate:

All expectations match therefore the implementation “works”.

Tao creates a test report summary:

In addition, Tao provides the test report detail:

The Devil Is In The Detail – Think Like A Tester!

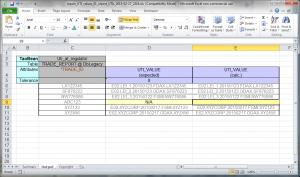

Until now, this is an example of test-driven development that focuses on the central use-case. I find many Business Analysts tend to “stop here” and focus on the central case only. I feel we just started describing the problem and the test-specification is not complete until we specify “corner cases”.

For this – we have to “switch hats” and think like a tester!

For example, what should happen if we have an account without a corresponding LEI value, or if the value is DUMMY? What should happen if the generated UTI value is not unique?

So it continues to the next layer of detail: what happens when two different accounts reference the same LEI? Is this a problem or does the business allow one LEI to open many different accounts for trading purposes? If many accounts exist, do we need to know about the account type (e.g. memo account, trading account, collateral account) and filter accordingly?

The more we “think like a tester”, the more value we put on high-quality / low-volume “variations” rather than multiple instances of the same theme.

Thus, we include “corner cases”:

Extend the account LEI map to exclude a mapping:

Consequently, we expect accounts with unknown LEI to report as N/A:

The Tao test-specification can grow quickly in diversity, independent of the IT development process and in collaboration with the business. Further, Tao retains all the value from previous use-case scenarios – nothing becomes lost, nothing becomes legacy and the each time the test runs, Tao validates the relevance of all previous analysis.

Assuming no further changes, Tao fails the test:

This fails because the implementation cannot translate the “unknown” account:

For the developer, this is the entry point they need for bug fixing. So long as the implementation passes the test, we do not care how we solve the problem.

Back to the Future?

Suppose we tried the same exercise without using Tao. I have to write a specification. Although I know what I mean, how can I tell that the developer knows what I mean?

For example, “build a UTI generator so that a source system trade identifier transforms to the E02 format. For each source system trade, look up the relevant LEI information using the corresponding account code and if not found the LEI information then return N/A, otherwise, concatenate the LEI with product, trade date and original trade reference.”

At what point will someone remind me that I forgot to mention “.” delimited values – I thought you tested it? What about the date format – you said done?

Recently I was “Tao-nising” a legacy implementation. I was amazed to see how fragile and how untested the legacy code was. How on Earth did it make to production?

When I am working with Tao, I can pass feedback to developers and focus them quickly to the entry points of failure. Recently, for specific trade constellations, the buy-sell direction for opening trades used different logic compared to trade valuation. What was reported as a buy was, somehow, valued as a sell. The developer applied an immediate bug fix and although he fixed that bug specifically, a previous test elsewhere suddenly failed. The bug fix introduced new bugs. Easy: feedback to the developer and let Tao re-run all tests to validate the definition of done. In the end, how can bug-free code not make it to production?

For me, Tao is a step forward going back to the future: going back to the old ways is too hard to do.