Let’s imagine that you were assigned to the new Test Automation Initiative. The product is mature enough but has little or even none automated-checks coverage. Product codebase consists of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) lines of code, and building a proper Agile Testing Pyramid is not an option anymore.

Even though it is clear that most of the automated-checks should be written on the unit level, writing them may be a challenging task. When writing testable code is not among the top project goals – codebase tends to become rather untestable.

Under such circumstances, Test Automation Engineers usually consider the only option which seems to be viable, which is to rely on the system-level automated checks (for example – UL-level checks), which often leads to the “Ice-cream” antipattern [1]. However, there’re some other options. While it may be already too late to build highly effective automated-check suite, there’re some good approaches to minimise reliance on system-level checking. One approach which may be very helpful in the situation like this is called “Feature test model”.

Revised terminology

There’s an old joke – if you get three experienced developers into the meeting room and ask them to define what “unit” is, you will end up with at least four different definitions. Currently, there’s no universally accepted definition of what “unit” is, and therefore there’s no universally accepted understanding of what good unit-level check should look like. There’re at least two different schools of thoughts on the matter (mockists vs. classicists) [2]. For the Test Automation engineers that subtle difference usually is not very important. In the research, done by Google to identify what automated checks from their codebase were flaky and why they actually came to the conclusion that one of the decisive factors was test size [3]. It may be easier to just break tests into three major categories as Google did:

| Check size | Heuristics |

| ————- |:—————————————————————-:|

| Small checks | Test logic confined withing one method/function/module or class. |

| Medium checks | Test logic distributed between more than one module or class |

| Big checks | Test logic distributed between more than one module or class and use external dependencies in any way (like DB, Web Server, etc). |

While the “revised” terminology may look vague, I found it actually quite helpful. It allows overcoming issues caused by a different understanding of what unit/integration/system level checks might/should be.

Feature test model aims to help with achieving following goals:

– Decrease reliance on Big and Medium automated checks

– Increase test suite speed and stability

Known limitations

This approach is specifically designed for the “dedicated Test automation engineer” set up. i.e. where there’s person\several people responsible solely for test automation. In other words, when developers don’t write test automation themselves.

However, one of the biggest disadvantages of this approach is that it requires a good deal of expertise and knowledge of software development and programming. In addition, being able to use coverage analysis tools may be very helpful as well. My personal opinion is that software development and programming knowledge is must-have for any senior Tester or Test Automation Engineer.

Implementing Feature test model

The algorithm itself is quite simple:

1) Identify feature

2) Find where this feature is actually implemented

3) Write the smallest possible automated check which checks this feature

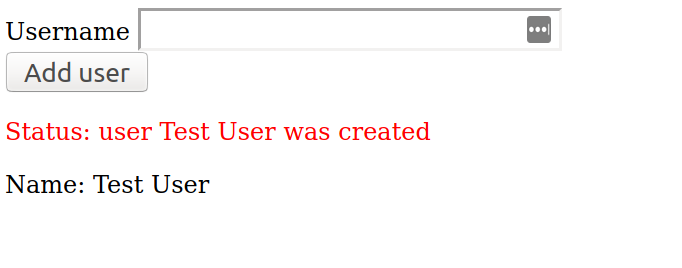

As an example, I suggest a simple application, that allows adding new users to the database (link to the repository with the application)

In addition to the possibility to add new users, this application provides simple input validation:

1) It will not be possible to add a user with an empty name

2) It will not be possible to add two users with the same name

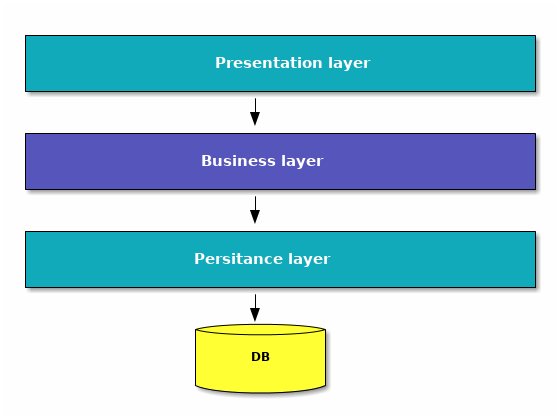

From the architecture standpoint, the application is a variation of 3-tier architectural pattern [4].

Identify feature

When there’s a story or piece of functionality which requires test automation – we should break it into atomic “features”. By feature in this context I understand some kind of requirement, which can be reasonably checked using a single automated check.

For example, for the application above, we can come up with the following feature list:

1) Add new user to the database

2) Print list of added users below the input form

3) Validate user input – write error if empty user name is given

4) Validate user input – write error if non-unique user name is given

Find where this feature is implemented

Add new user

It is a fairly complicated functionality, which requires quite a lot of classes to interact properly with each other. It starts with processing the input from the UI, passes through the validation logic and ultimately uses all levels of the 3-tiered architecture of the application. To check this feature we will have to write a big System-level test.

Print list of added users below the input form

This is also quite complex functionality, which uses all 3 levels of the application. Many test automation engineers would combine checks for this functionality with the previous one. In this example I also combined those checks:

```java private SelenideMainPage sut = SelenideMainPage.INSTANCE; ... @Test public void shouldBeAbleToAddNewUser() { sut.setUserName("MyCoolNewUser"); sut.clickSubmit(); Assert.assertEquals("Status: user MyCoolNewUser was created", sut.getStatus()); Assert.assertTrue(sut.getUsers().contains("Name: MyCoolNewUser")); } ```

The full code may be found in: `LoginFormTest`

Validate user input – write error if empty user name is given

Depending on how this validation is implemented, it may be either:

– small Javascript check, if validation is implemented on the Javascript level

– medium Java check, if validation is implemented on back-end side

– Big Java check, if validation logic is implemented some insanely-complicated way

In our case, we can implement this as medium Java check as there’re only a couple of classes involved in this validation check:

1) “`business.service.UserService“`

2) “`business.validation.EmptyStringValidator“`

```java @Test public void shouldNotBeAbleToAddEmptyUserName() { final Map usersBeforeTest = sut.getUsersList(); final int numberOfUsersBeforeTheTest = ((List) usersBeforeTest.get("users")).size(); final Map myCoolNewUser = sut.addUser(""); Assert.assertEquals("Login cannot be empty", myCoolNewUser.get("status")); Assert.assertEquals(numberOfUsersBeforeTheTest, ((List) myCoolNewUser.get("users")).size()); } ```

So, instead of testing the whole application, adding browser/server/http overhead, we create medium-sized check and use `environment.UserApplication` as an entry point.

Such check still would check almost all the application, but would still be much smaller and faster in comparison to UI-driven check. This approach is often called _subcutaneous testing_[5].

Full code: `environment.UserApplicationTest`

Validate user input – write error if non-unique user name is given

Even though this feature looks more or less identical to the previous one, the code implementing this functionality is slightly different:

1) “`business.service.UserService“`

2) “`business.validation.LoginValidator“`

We have already tested most of the logic related to error handling in the “`UserService“`, so we can cover this functionality with even even smaller Java check.

```java

@Before

public void setUp() {

sut = new UserService();

sut.setUserRepository(new InMemoryRepository());

}

@Test

public void shouldNotBeAbleToDuplicatedUser() {

final List users = sut.getUserInfoList();

Optional validationStatus = sut.validateLogin(userName);

Assert.assertTrue(validationStatus.isPresent());

Assert.assertEquals(userName + " user is already present", validationStatus.get());

}

```

In this case, we bypass `environment.UserApplication` and check `business.service.UserService` directly, making the check smaller and faster. Besides, we were able to stub DB, which will make check even faster.

As a result, we would end up with 3 automated checks, 1 Big and 2 Medium. It also would be very interesting to compare this test suite with the alternative ‘UI only’ approach.

My benchmark figures:

Total test run time: ~ 10 seconds

Code coverage: 90%

In comparison, if we had written 3 UI-level automated checks for the same functionality, we would have ended up with the following parameters:

Total test run time: 23 seconds

Code coverage: 87% (Even smaller value, because UI-driven test cannot execute `environment.UserApplication.deleteAllUsers()` method, not available on the UI)

Conclusion

Using Feature test model it was possible to make automated test suite more than 2 times faster, without sacrificing code coverage. Even more, this approach gives better granularity and control over System Under Test. The feature test model can be implemented relatively easily too. Full code can be found here.

References

[1] “Testing Pyramids & Ice-Cream Cones”

[2] “Test Driven Development Wars: Detroit vs London, Classicist vs Mockist”

[3] “Where do our flaky tests come from?”

[4] “Software Architecture Patterns by Mark Richards”

[5] “SubcutaneousTest“